Building Community

Before I was a teacher, I was a student, an eager one. To me, school was a safe and orderly place, in contrast to life at home. When I graduated from high school, a first in my family, I chose a college far away from home. My experience as a first-generation student informs my approach to teaching, sometimes in ways that still surprise me.

When I told my father about my own college plans, for instance, he looked at me as if I had just grown a third eye. “I just don’t understand,” my older sister said. She suggested I start hanging sheetrock with my brother, or get a job in the shoe factory where my other sister worked. Not everyone believes in a college education, and this attitude is passed down from one generation to the next. As college teachers, we have bought into the idea that getting a college education is a good and desirable thing, but this belief itself is culturally derived. “Where are you going to college?” is a question many young people never even hear, especially those from disadvantaged communities. For these populations, college is not on the radar at all. When it does pop up, it may seem to them like a pipedream. Now, when I walk (or “zoom”) into my FYW classroom as a teacher, I take this knowledge with me: many of the students in front of me have already exhibited true acts of bravery by simply showing up. Once within the academy walls, they might feel like I did as a first-year college student— alone, without a peer group, and without a support system at home.

I, for one, was a hot mess my first year of college. I felt like I didn’t belong. I didn’t know how to navigate the strange world of the academy. Doing well in classes was only part of the puzzle, a puzzle that the other kids seemed to have already figured out. I coped by tuning out. I skipped classes and rolled out of bed during the afternoon hours, just in time to make it to the dining hall for lunch. I blew off assignments and filled out multiple choice exams as if I were wearing a blindfold. What turned it around for me was that by the end of my first year, I had finally found a peer group comprised of odd balls like me, who could help me up when I fell. I was no longer alone. Valuable research in the field of pedagogy also points to the same conclusion: student success and a sense of belonging go hand in hand.

That is why I privilege community-building as a necessary precursor to student learning, on day one of my FYW sections at Florida International University (a diverse, minority-majority institution where my university teaching experience lies). Up front, I take a poll of the class, to see if anyone knows anyone else. Usually, we’re all strangers. I openly acknowledge that before I lead the students in a series of “Get to Know You” exercises designed to a) build community b) introduce core rhetorical concepts and c) get students writing.

The sequence goes something like this: first, the students pair off and interview each other, with guiding questions provided. Second, they write biographical sketches of one another, based on the notes they took during their interviews. Third, I invite students to share their sketches with the whole class. Fourth, I introduce a new genre, the recommendation letter, and give the students time to draft one. Fifth, we share again. Sixth, to assess student learning and encourage metacognition, students write a guided reflection on the entire process. The last step is a whole-class discussion of take-aways.

These exercises generate a palpable change in student demeanor, a positive one. When I read the room afterwards, I see more smiles, and more relaxed bodies. There’s more eye contact, less staring at phones, and side conversations have started to crop up. At this point, I also give time in class for students to exchange contact information, or set up a group chat, so that they can communicate with one another outside of class. “We’re all in this together,” is the refrain.

One moment always reminds me that community-building in the FYW classroom pays dividends. It was about ten minutes into my ENC 1101 class. I was introducing the first activity, when a group of five students showed up all I once, skateboards in tow. At the end of the class, they came up to me as a group and explained their tardiness. It was because one of the five was struggling, and had planned to blow off class. Instead of coming to class without the one, the four rallied behind him and brought him along. I blew off my own share of classes as a first-year college student, before I had peers who would knock on my door. Bringing up the ones who fall behind, the ones who struggle— that is teaching’s imperative, and challenge. Active community-building helps.

Building Critical Thinking Skills

I am not as naïve as I once was, but I remain convinced that postsecondary education is a solid way to empower young adults, or learners of any age. That may mean improved job prospects for some, while for others it may mean improved habits of the mind that they can take with them wherever they go. Two such habits that I privilege in my FYW classroom are thinking critically, and cultivating a growth mindset.

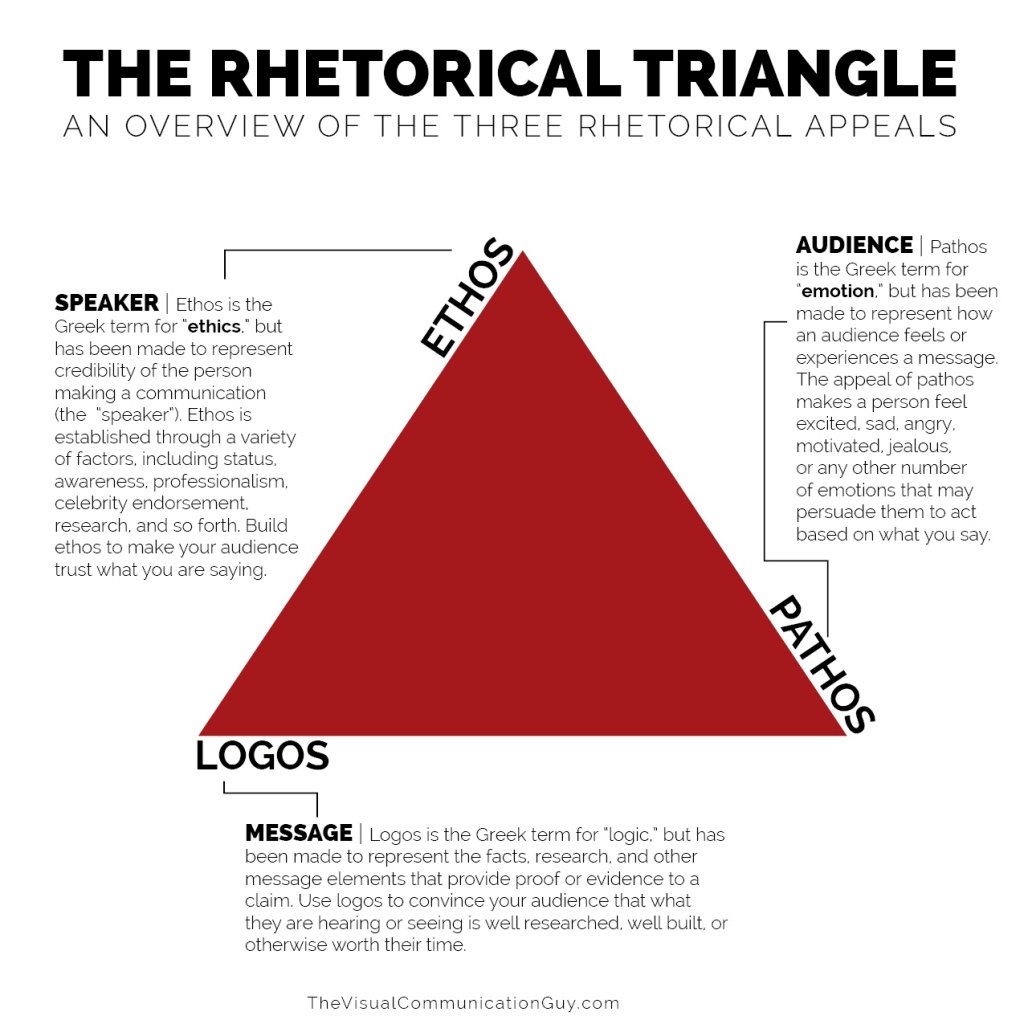

Thinking critically for my FYW students involves rhetorical analysis, conducting responsible research, and making smart writerly choices. Critical thinking also involves not believing everything you see, hear, or read. We live during what has been called “the information age,” an age in which the contemporary college student is bombarded with rhetoric. This rhetoric is not always helpful, accurate, or true. Current events show the damage that can come from rhetoric turned to bad purposes, as well as the good that rhetoric can do. I want my students to be able to spot the difference, in others’ rhetoric and their own.

It takes practice. One in-class method I use is an information literacy exercise borrowed from the Stanford History Education Group, and designed by FIU’s Jackie Amorim. Students are asked questions about a series of images, to gauge their information literacy. Are they able to spot the differences between advertisements and news articles? Do they know what “sponsored” content is? Are they misled by images taken out of context? Do they recognize the signs of salesmanship, such as a play on emotions, or creating a sense of urgency?

The image of the “Fukushima Nuclear Flowers,” always draws a lively, sometimes passionate class conversation. The image of the strange, malformed flowers is accompanied by the caption, “Not much more to say, this is what happens when flowers get nuclear birth defects.” But who knows where the picture was taken? Or when? Maybe the flowers were just born that way, and Fukushima had nothing to do with it. No one likes to be fooled, and after this “aha” exercise students are already on the lookout for spotty rhetoric.

Cultivating a Growth Mindset

When students cultivate a growth mindset, they realize that they can learn, grow, and build skills, no matter their starting point, and particularly when it comes to college writing. A growth mindset places process over product, and sees mistakes as opportunities to grow. This value is reflected in how I assign, assess, and frame academic work in my FYW classroom, which is anchored by three to four major writing projects. I scaffold assignments so that they build upon one another, with low stakes writing tasks near the beginning of the sequence. This design allows for periodic feedback, and introduces students to course content in a pace that helps them develop a writing process and grow confidence. Emphasizing growth rather than perfection, I offer milestones due dates, and multiple opportunities for revision. I aim to cast writing as both a process and knowledge-making endeavor, a journey rather than a destination, one that culminates in a guided reflection.

Such reflections (along with student-facing rubrics for all academic work) are good for my students, and they are good for me. Reflections help students with retention of skills, so that they can carry forward what they learn in my class. Reflections also allow me to assess student learning. I have often learned from student reflections when I need to adjust my teaching style, or revisit a “muddy point” in class. I also use the “Ask It Basket” to assess student learning, and I try to make it fun. I project the “learning outcomes” for the unit onto the screen, and give the students time to read them. Then I ask them to think about whether they believe they have achieved these outcomes. After that, I invite them to write a question on a slip of paper, fold it up, and drop it in a basket, which I am walking around the room with. After everyone has put in their question, we take turns drawing them from the basket, and answering them as a class.

There have been no stupid questions.

Practicing What You Preach: Teacher as Student

Finally, I let students know that I am a co-learner with them, and that I don’t have all the answers. I try to practice what I preach, and show by example whenever I can. In my FYW classroom, this means that I am both a student and teacher of writing at the same time. Students know this when I teach brainstorming and other writing techniques. One technique is the use of mind maps to generate, connect, and explore ideas during the pre-drafting stage of the writing process. I tell the students the narrative of how I first learned about mind maps, when I started to use them, and how I have used them since. Then I pull out the disheveled manilla folder of my own mind maps, and show a few on the document projector. They are messy, weird, and sometimes illegible. We talk about them. The effect is that my credibility with the students goes up, and they are more likely to be more engaged when they practice their own mind maps afterwards.

Teachers are students too. We too fall prey to some of the same obstacles to deep learning. To overcome these obstacles, we can reach for the same tools we may espouse in our classrooms. A growth mindset, for example, tells me that there is always more to learn, and that failure is a path to growth. Progress, not perfection, is the mantra, and I am free to experiment with teaching strategies that sometimes work and sometimes don’t. A growth mindset also tells me to seek feedback from my students, and to be responsive to this feedback. To date, ongoing professional development workshops, teaching circles, faculty book groups, and faculty mentorship initiatives at FIU are some ways that I stay engaged as a lifelong learner and participant in the field. These exchanges also help me build community, renew my own buy-in to the teaching endeavor, learn in collaboration with my peers, and apply critical thinking to my own teaching methods. The aim is always better teaching, and better learning. To me that means fostering habits of mind in my students and myself that will empower us beyond the classrooms that, for a brief time, we share.